Discernment and Community in the Twitter Age

A presentation for Dominican University’s Siena Centre’s Albertus Magnus Lecture series

October 13, 2011

Good Evening,

I’m grateful for the opportunity to come to Chicago and speak to you tonight … I have long admired your university in the personalities of a number of good friends that have worked here, and, ever since my own graduate education at Loyola University Chicago, the general approach of Roman Catholics to the pursuit of wisdom. There is, to be sure, a wisdom in my own tradition, the tradition that I am here to talk to you about tonight, but it is not as organized, and therefore surely not as celebrated at the work of your society and the larger tradition which holds it. So let me offer my unabashed thanks for your being you. And to … for facilitating this pursuit of wisdom in hosting me here tonight.

My tradition has a generally dim view of education. The most conservative of these groups stop formal education in the 8th grade. The most liberal of these groups sponsor their own colleges and seminaries, like the school I teach at in Bluffton, Ohio, but in order to gain education beyond the master’s level in disciplines other than theology, peace making, education or curiously business, I needed to set out on my own path and attend a Catholic School. I could have gone to a state school or a protestant school, but, really, why would I have done that? Mennonites now have doctorates in many fields, but Mennonites with doctorates are held with more suspicion than celebration in the church that we belong to.

Why is this?

It is not that we don’t value wisdom, or learning, but that the type of wisdom and learning that is valued is that which can be made plain to anyone.

Specialized theories, or methods, or equipment or cynicism; the stock and trade of all advanced academic work; are always held suspect because these methods can contain their own kind of pride, the discussions they entail exclude some people and they are not therefore generally observable, and, they might suggest an approach to the world which is doubtful rather than yielded.

Knowledge about the bible, about the history of the tradition, about how to farm, or raise a family, about how to build up community, to walk simply on the earth, to avoid conflict, to follow Jesus; these things constitute wisdom.

In my journey at university towards tenure and promotion, my service to the church in publications in church periodicals, sermons at churches, or service on church committees is valued as much as publication in esoteric academic journals. There are a number of Mennonite academics who have rejected positions at Harvard and its ilk to continue serving at a church school.

If I needed to discern the central theme in Amish and Mennonite life that informs our approach to new information technology it is something very much like what I’ve identified here: humble and plain, open and yielded.

So I’d like you to notice three things in what I’ve said so far. There is a spectrum of Amish and Mennonite approaches to similar questions. There is a general suspicion of worldly ways of doing things. I really like how you do things; which pins me on one extreme end of the spectrum.

Let me begin again; this time with a little history, so that I can locate the topics that I want to connect tonight, and give you a few points of departure.

The early 16th century was a time of huge political, social, religious, and technological upheaval. I doubt living then felt anything like living now feels, but historically the 16th and 21st centuries have real commonalities. The invention of the printing press poised society on the cusp of great change. The religious reformers of the 16th century took advantage of this change by translating bibles into the vernacular and opening up questions about the nature of religious authority.

Luther and Zwingli are the well known figures at the vanguard of this change and each saw their movements gain state support and solidify quickly into institutionalized movement which loosely paralleled the existing catholic church.

At the same time a group of even more radical reformers in Switzerland and Germany started to coalesce around several interrelated ideas: adult baptism on confession of faith (hence the term Anabaptist which means re-baptizer), strict adherence to the scripture as interpreted in the spirit’s presence in community, and a simple life marked most particularly by refusal to act violently. Anabaptists were yielded to their faith in baptism, to each other and scripture in their interpretation, and to their enemies in their pacifism. They were in the most part plain, open and yielded.

The refusal to act violently and adult baptism parts clashed starkly with all other forms of religious and social organization at the time. Adult baptism is inherently democratic and it can establish a kind of community that can, due to the voluntary initiation of its members, expect much of its followers. Pacifism has always been distrusted by authorities responsible for the maintenance of social order. These two things together suggested, probably quite accurately, that these Anabaptists could not be trusted. In 16th century Germany, much like 21st century Syria or Tunisia, this meant death to dissidents. Anabaptists were killed en masse, and the stories of these martyrdoms gave this movement both confidence in its convictions and a quietest spirit. Under the leadership of Menno Simons who saw that the movement would need to go underground to survive, the radical Anabaptists of the 16th century gave way to the Mennonites of the 17th. At the end of the 17th century Jakob Amman, concerned with lax discipline among the Swiss Mennonites of his day, led a schismatic element away from the main Mennonite church. At the beginning of the 18th century many Mennonites and Amish emigrated to this country. Their beliefs and practices were in the most part similar but developing along two parallel tracks.

The reason I can stand up here operating a powerpoint giving a talk written in equal parts on my MacBook Pro and iPad2 after having driven here this morning in my car without embodying contradiction is a set of schisms that occurred in Mennonite areas in Canada and the United states at the end of the 19th century. Educational reforms like Sunday School, increasing acculturation and technology use among Mennonites generally led Old Order groups to separate in order to preserve their communities as they knew them.

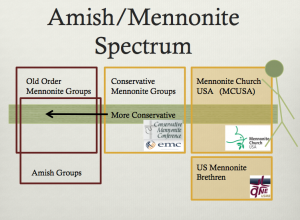

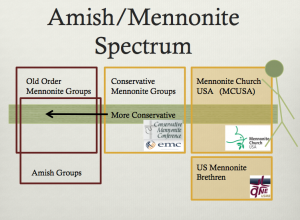

So here is a graphical representation of the spectrum of groups that I’ve been talking about tonight. All of these groups exist in decent but very moderate numbers in the USA today. There are 250,000 Amish, 40,000 Conservative Mennonites, and 110,000 in the Mennonite Church USA and 30,000 in the Mennonite Brethren. There are probably about 100,000 Old Order Mennonites but they are really uncounted.

There are four Mennonite denominations. Mennonite Church USA and the US Mennonite Brethren are the most liberal and have relationships and communications with churches both Catholic and Protestant. Then there are two very small denominations, the Conservative Mennonite Conference and the Evangelical Mennonite Conference. There are also many other conservative Mennonite groups that are not unified by any kind of denominational grouping or relationship to other churches. There are probably an additional thirty groups of in each of the Conservative Mennonite, Amish and Old Orders boxes on this chart. So, It’s not like the plurality of Catholic Religious Orders but there is still probably a joke in there somewhere. There is no Amish or Old Order denomination. There are again many different groups as the Amish and Old Orders are very schismatic often dividing over questions of technology use. The divisiveness of Amish and Old Order Mennonites is an interesting aspect of their discernment. Sometimes, almost in order to explore two different patterns of community life, a community will choose to divide intending to reunite when they can. Sometime this happens within 30 or 50 years, sometimes hundreds of years later, sometimes not at all.

The really noticeable difference between Amish and Old Orders and Conservative Mennonite Groups and the Mennonite Church USA, marked on your chart by the difference in color is that the Amish and Old Orders are plain. They wear plain dress, drive horse and buggy, or perhaps a car with its bumper painted black to emphasize its plainness. Conservative Mennonites and the MCUSA do not look any different from the rest of society. We are not plain but simple.

For all Amish and Mennonites the church is the basic and fundamental religious unit, more important than regional, national or international relationships, even if those other relationship are important. The Mennonite Church USA does meet bi-annually to conduct business by delegate session, but even the statements it issues are always seen as provisional. We think that the Apostles Creed was well written but basically we are a group of confessional not creedal churches.

I said earlier I was on one extreme of this chart. Here I am.

This rock and roll (that is, highly selective and abbreviated) history will have to suffice in order to introduce you to my people. It would be too much to develop the patterns of discernment and community among all three groups simultaneously, so let me instead seek to work on two topics in succession. First, how do Amish and Old Order Mennonites engage technology. Second, how, or should, Mennonites, for that matter any Christian, engage technology. To do this I’m going to propose three rules. These rules are genuine, in that I think they should be, in that I do them and in that they practice an approach that is yielded to technology. But the are kind of funny, and I offer them cognizant that I’m not in regular patterns of accountability with most of you. I’m easy to ignore. Having done my due diligence to the world as it actually is let me from now on use “Amish” for the conservative end of this spectrum and “Mennonite” for the other end.

I think that the interest in the Amish in terms of their approach to technology is explained well by questions like these, taken from the description of this series of lectures.

Can theology articulate ethical norms for the development and use of technology in a way that will protect the integrity of creation and the dignity of the human person? Has our culture forfeited its responsibility for prudential judgment and moral restraint in the face of dazzling scientific discovery? How do we begin to think through the potential side effects of scientific advances before moving ahead with blind optimism?

If we are really concerned about things like ethical norms for the use of technology, a forfeited culture, moral restraint, potential side effects and blind optimism, then it makes sense that we attend to a culture that by all appearances has not forfeited its responsibility to engage in moral restraint and is the very opposite of blindly optimistic about technology.

The horse and buggy is a symbol of moral restraint and technological withdrawal. However the truth about the Amish is much more subtle that this. They have not simply withdrawn from technology. They have withdrawn, that is separated themselves from, the world. Not the world as created by God, but the world of human society. The separation here is from all that is profane into a sacred community in which you are expected to do everything you can to live as if the Kingdom of God were here now. By way of the eucharist Catholics move from the profane to the sacred weekly at mass. In general, Amish and for that matter Mennonites, do this once, at baptism. All things are always sacred for the Amish, although the term sacred would come off as a bit haughty to them. The Amish use of technology is therefore all about building that community. Donald Kraybill suggests the Amish interact with technology in three ways: acceptance, adaptive, and rejection.

The Amish are happy to accept new technologies from battery operated calculators, to inline roller skates to gas barbecues as long as they are deemed helpful and benign to the community. Notice that there is no threat to community from any of these technologies.

Other technologies can be accepted if they can be adapted to the regulations of the community. Amish communities are governed by the Ordnung, an unwritten oral collection of rules and regulations that govern the life of the community. These are absorbed by young people informally as they grow up and accepted at baptism. Understandings of technology become adopted into the Ordnung. For instance, Tractors are a problem because they act too much like cars and cars take you away from your community, and isolate you while you are inside it. Some communities allow tractors but only with steel wheels. That way they can’t be taken on the road. Some communities have adapted to tractors with pneumatic tires as they have acculturated to the difference between tractor and car. These communities would all have different Ordnungs but everyone would know exactly what was accepted and not. If a member strayed from the consensus, or if the community decided that their technology was offensive, they would be asked to put the item in question away, that is, to sell it.

Technologies that encourage agriculture or business are much more easily accepted. Balers are retrofitted with gasoline engines that can then be pulled by horses. Pneumatic powered tools are becoming more an more common, typically running off of gas generators. Electricity is run to barns (but not houses) in order to keep milk cold to meet state regulations. In each of these cases compromises are made in order to either allow farming to continue or to increase agricultural efficiency without changing the mode of agricultural production.

The Amish will quickly reject technologies that will likely be detrimental to the community. Communication technologies are more carefully screened than any other type of technology because of the connection to the outside world and its corrupting influences. Television’s one way conduit into the home is probably the most egregious example of a corrupting influences. I know many Mennonite homes that won’t have a television for the reasons that there simply isn’t enough that good to watch on TV. The similarity between a television and a computer monitor is one of the primary reasons that computers were initially suspect. Like the old joke that Mennonites won’t have sex standing up because it might lead to dancing, the Amish initially rejected the computer not because of its own potential problems but because it seemed too much like television.

Kevin Kelly suggests four aspects to how the Amish make decision around technology. They are selective. They evaluate new things by experience instead of by theory, and they reject more than they accept. Innovators pioneer the adoption of new technologies but the community makes the final decision. The maintenance of the community and separation from the world are the leading factors in making these decisions.

These factors end up with a situation in which for at least some Amish, technological experimentation is the rule and not the exception. Electricity is typically banned because it connects the community to the outside world and creates an unacceptable dependency. Some innovate by utilize electricity that comes from 12 volt sources from batteries rather than 110 volt power from public utility lines. Others use gasoline powered pneumatic technology is then adapted to run anything from kitchen blenders to entire wood shops.

Note the importance of surveillance in this example. The Amish are not, at any point, going to create their own batteries or gasoline. But gasoline is a consumable that can be purchased, along with other supplies, and used in discrete amounts. At least part of the problem with electricity is the wires that run from the road to the Amish persons house. The plainness of the Amish life is very environmentally sensitive, but environmentalism is not the point, community is.

Surveillance is also important in thinking about the use of telephones among the Amish. Having a telephone is not necessarily a problem. It facilitates business calls and can be helpful in emergencies.

The Amish do not want to depend on the world, but they are not fatalistic either. They will use hospitals even receiving expensive advanced care. They won’t hold health insurance, preferring to pay in cash for the services rendered. Sometimes, the community needs to extend a broad net to collect enough to pay a bill. Individual debt is no problem for the Amish, as long as it was not incurred by the individual.

Having a telephone inside your house allows for non-surveillable telephone conversations. Having a telephone shack built out by your shop or barn is more open and yielded. Some of these phone shacks can be very nice built with space for more than one person. It can be nice to have someone wait with you in the rain. These conversations need to be scheduled in advance. Cell phones then create an interesting quandary. They are even more surveillable, as anyone who has ridden on the CTA knows. But they are also much more individualistic, which is not a good thing. The community member who only uses their cell phone in the presence of others would be even more virtuous than the person who talks in a phone shack. Still, most telephone calls are to the a business contact in the outside world. Telephoning another Amish would be seen as detrimental to the community because it replaces a visit. The Amish look to innovators to test new technologies and the innovators, often people who really enjoy technology, get to use the new things for at least a little while. The innovator needs to be careful though because every member is also the reputation of the community. The Amish person becomes who they are through interactions with other people.

The responsibility for managing this experimental consensus and overseeing the Ordnung lies with the bishop. A functional bishop does not set the direction for the community but rather knows what the most conservative member think and moderates a compromised position that accepts, adapts and rejects according to what the whole community can live with. I say compromised, but yielded would be a better word. The best general example of this is in the pattern of use rather than ownership among the Amish. Many will much more easily use a technology than own it. It is much easier to be yielded to something that you don’t own.

Finally, its important to note that there are points in which the Amish as a group are technological pioneers. I mentioned earlier that the martyr stories are very important to Amish and Mennonites. These exist in a book called the Martyr’s Mirror. In 1745, Jacob Gottschalk, the first Mennonite bishop in the Americas, arranged with the Ephrata Cloister to have them translate the “Martyrs’ Mirror” from Dutch into German and to print it. The work took 15 men three years to finish and in 1749, at 1512 pages, it was bar none the largest most technologically significant publishing venture in the Americas. When the technology is needed, there is not hesitation, even among the most conservative Amish to employ it.

The technology then is never evil intrinsically from an Amish perspective. In this way they have absolutely no Luddite tendencies. Technologies are all simply instruments which are either used for ill or for good.

It is helpful here to make a distinction between instrumentalism and determinism in reference to technology. To put it simply, determinists believe that technologies have inherent values. Our tools shape our use of them for good or ill, perhaps more than our intention. Determinists believe that the fast pace of our society is because our tools promote speed. Determinists believe that guns kill people. When people don’t think about how they use technology they aren’t going to be able to control it. It will control them.

A strict instrumentalist believes that technologies have no inherent value. How we use the instrument shapes the morality of its use. Guns don’t kill people. People kill people. Cellphones aren’t irritating, people who use cellphones are irritating. Partly because I am very optimistic about the possibilities that come with new technology, I think that the best thinking about technology is modified instrumentalism. I do definitely believe, with the determinists, that some tools shape their users. The difference between the gun and the cellphone is important. Guns are only good at killing people or at least injuring people. When guns are used for protection, defense, or safety, they do so by killing or threatening to kill people. Guns have determined uses. Cellphones are less determined.

An Amish person would never develop this philosophy of technology but in the end we would be in quite close agreement about how to make decisions.

There are many similarities, I think, between how I think about technology and how an Amish would. The key difference is that my community does not become offended by my technology use. People make fun of me when I play video games, but noone suggests I stop, or play differently. This is the difference between plain and simple. This is perhaps where we have forfeited our responsibility, by not calling each other to account for how we use technology.

So, how do we get it back?

Accept, for the purposes of this evenings discussion, an argument that I want to make but don’t have time to develop. The yieldedness of the Amish from technology to allow for the unencumbered forming and maintaining of community is analogous to the yieldedness of a Mennonite to technology in searching for technological utility in forming and maintaining community. You can substitute in any other faith for Mennonite in my analogy but you need to retain a focally central community.

If this analogy holds then the responsibility of our community is to find ways to use the technologies that we encounter to build rather than isolate ourselves from each other. I’m going to talk about three technologies that are relatively new and suggest a few rules for using them as a way of concluding this talk.

I’m not going to talk to you about facebook because Cathi Falsani did that last year. But I think you should all have facebook accounts. Here’s why. We think that it is responsible for details of our lives to be kept private from others. And, in some ways, privacy is really important. We need to protect our children and other vulnerable people from exploitation and the kind of information you can get on the internet surely facilitates some kinds of exploitation. But in general, I believe that the question of privacy is a red herring for Christians. We should not have anything to hide. On the contrary we should want everyone to know and be converted by our lives. This is why I think that every Christian should be on facebook.

Using facebook as it is now is not particularly virtuous, but we have difficulty in the church with privacy, with individualism and with money. Would it be a good discipline if we again shared, as I’ve heard we once did, our yearly income and tithing? What if churches built a small web applications to add to our facebook pages that reported our individual income to other members of our small group, congregation or diocese. Or if we didn’t want to use facebook, what if this kind of functionality were standard on church websites, even if it were in a members only system. My point is that the kind of sharing that facebook encourages could really strengthen bonds of Christian friendship and accountability in important ways if people committed to using the technology carefully.

Twitter took the internet by storm a couple of years ago. It is made for cellphones since all it can do is post messages 140 characters in length, or less. I’ve noticed that when I read something that comes from someone I trust I am willing to spend much more time on it. Twitter, at first glance, might seem like the worst offender in the contest for dividing up my attention, which can be a problem with the internet as anyone who has read Nicholas Carr’s Is Google making us stupid knows. But on the day of the awarding of last year’s Nobel Peace Prize I was reading things written by Liu Xia wife of the awardee Liu Xiaobo. The best coverage of the fall of the Tunisian government was hosted by the quirky website boingboing. People I respect on twitter had compared various coverage and posted this. It became easy for me to read exactly what I wanted to on the subject. This was for me much more dramatic on the night Osama bin Laden was killed. Because of who I follow I mostly read calls to not glory in a human beings death.

Of course the role that twitter itself played in the actual fall of the Tunisian government is much more significant. Youtube, facebook and twitter convey information and ideas at light speed around the world. The internet is probably the most important tool in making globalization happen.

It is also a tool of destabilization for governments the world over. Inflexible regimes like the one in Tunis fall and twitter is as important a tool in doing this as any other single too. Stable, flexible governments like Sweden or Switzerland aren’t affected as much. It remains to be seen how countries like ours will fair and the Occupy Wall Street Protests are a key example of this. One thing that is really interesting about the Occupy Wall Street internet presence is that it is driven in part by twitter, but twitter is also an instrument in spreading confusion and misinformation about the protestors. A twitter mob is easy to start if people join in, but a twitter counter-mob is just as easy to start if people join in. A number of the hash tags that people have used to spread information about Occupy Wall Street have been coopted and spread confusion rather than instruction.

To the extent that Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was an evil dictator, I’m glad he’s gone. If regime change means a better life for the poor, the widow, the orphan and the alien in that country we can be grateful to twitter. However in the end, as Christians, while we are concerned about the world we should not place our hope in twitter. Our hope in is God. Still, if we learn how to use it twitter might become a better news source than CNN, NPR, or the Vatican. It could do this just because it combines information for each of these sources. Should we insist that our leaders tweet? Christians need to be able to talk publicly about their faith. Our leaders already need to be good at this. So one of my rules, but I say this somewhat tongue in cheek, and only with respect, is that the Pope should tweet. I also think that the President Carroll, Vice President Kennedy, Provost Johnson-Odim, Dean Carlson, and other thought leaders on campus should tweet as part of their jobs. These should not be purely information accounts. They should be both personal and professional.

My last rule, is that you should play or that you should watch someone with more experience play Glitch. I suggest Glitch because it is social, free, non-violent, and highly imaginative. Actually, any Massively Multi-Player Online Game will do. Next Tuesday you’ll be able to play as a pet on The Sims 3, and there are priest characters on World of Warcraft. All you ever have to do is heal. These environments are typically very highly developed and very compelling. I remember once after having spent much time navigating the world in World of Warcraft in my night elf priest avatar (a really tall character in the game), navigating the world in a gnome avatar (a really short character in the game). At one point you need to get onto a boat. I felt viscerally like I was going to fall in the water because my legs were too short.

Before you think that I’ve come totally unhinged, consider the importance of practice and imagination. The Christian life is one that demands great imagination if it is to be done well. This is all the more the case when we try to live this life in the world. To some extent the great virtue of Amish life is that it contains the imagination. The imagination of the Amish community is real but bounded in ways that mine yours simply isn’t. How can I practice at having an unbounded imagination? One good way to exercise my imagination is to interact with others in a virtual space. Jane McGonigal, in her book Reality is Broken, suggests a number of fixes for our real world that playing games effect.

Let me list just a few

• Compared with games, reality is too easy. Games challenge us with voluntary obstacles and help us put our personal strengths to better use.

• Compared with games, reality is depressing. Games focus our energy, with relentless optimism, on something that we’re good at and enjoy.

• Compared with games, reality is lonely and isolating. Games help us band together and create powerful communities from scratch.

• Compared with games, reality is unambitious. Games help us define awe-inspiring goals and tackle seemingly impossible social missions together.

Rich online environments, like those found in good Massively Multi-Player Online Game, have real benefits. For instance, an important part of my Christian life is my pacifism. Games like Glitch could be a good opportunity for me to get practice at virtues like pacifism that are hard to practice in the everyday world. Imagine if games put me in situations that I didn’t anticipate but could navigate without using force. Glitch does this. Could I carry my skills from the game into real life? Well, NFL football players have been adapting their real world game play based on skills that they have learned by repeated playing of their own characters in games like Madden Football. There was a runner who burned time on the clock in a real NFL game by running along the 1 yard line before scoring a touchdown; a move which would have only seemed like risky grandstanding had he not discovered how well it worked in the video game.

These games are also very social. The computer manages the participation of a massive number of simultaneous real world participants. If we all had laptops could all go onto Glitch right now and play together, interacting with each other and many other people in the game world. How would this shape our interaction with each other. You might be sitting by someone you don’t know right now. But you probably aren’t going to talk to them after my lecture. A game might make you practice modes of interaction that the Apostle Paul avers for all Christians. It might show those modes of interaction to many many people.

What would it look like if churches held a annual game playing day? Experienced and novice game players could gather for a day, play, but then talk about how community was formed or maintained by the day. What if the results of the day led to decisions to then use or refrain from using particular games. I’ll admit that I don’t know of Christian communities that do this. And we can’t count on the Amish here. There is a seriousness and boundedness of their pattern of community that is not open to this type of discernment or play.

Actually, in some ways I think that in the stewardship of your imagination you are already somewhat ahead of me. Your university has a Vice President of Mission and a Centre like this one where you can explore ideas like this and keep your mission and purpose close at hand.You can explore the possible uses of science and then discern it’s use in a community. Blessings in this work and in all that you do together.

All summer long those Roosters abundantly frolicked, hung out, ate, drank, roosted, pecked, clucked and generally lived a good life. This life was only possible for these individuals if it ended with their becoming meat. They would not have been brought into existence otherwise. My friend Dave cares for these animals, feeding them the right amount of food and supplements. He gives them limestone for their gizzard (without it they couldn’t “chew” their food). And he knows how to kill them well. I didn’t take the knife that morning partly because it wouldn’t respect the rooster; their death came about more easily given Dave’s experience. Even so, his cut was a bit less decisive for the first of five roosters, and, as he was dying, he craned his neck up and met my gaze.

All summer long those Roosters abundantly frolicked, hung out, ate, drank, roosted, pecked, clucked and generally lived a good life. This life was only possible for these individuals if it ended with their becoming meat. They would not have been brought into existence otherwise. My friend Dave cares for these animals, feeding them the right amount of food and supplements. He gives them limestone for their gizzard (without it they couldn’t “chew” their food). And he knows how to kill them well. I didn’t take the knife that morning partly because it wouldn’t respect the rooster; their death came about more easily given Dave’s experience. Even so, his cut was a bit less decisive for the first of five roosters, and, as he was dying, he craned his neck up and met my gaze.